How to avert writing tedious test case documents through comprehensible Living Documentation

In this two-piece blog article, I share my experiences using Living Documentation as basis for customer acceptance tests for implementation sign-off.

In this two-piece blog article, I share my experiences using Living Documentation as basis for customer acceptance tests for implementation sign-off.

What we did to achieve a comprehensible Living Documentation

- Have a clear structure in how you organise your feature files (see part 1)

- Scenario titles describe your specifications (see part 1)

- Explain your documentation approach to readers

- Living Documentation needs to be current, complete, and accessible

In my first article I discussed how the structure of Living Documentation improves stakeholder buy-in.

In this second part, I share what else has helped to allow stakeholders understand all the information presented to them through Living Documentation.

Explain your documentation approach to readers

When we introduced Living Documentation as an alternative to test case specification to our customer, we were not very coherent about the terminology we used. We talked about Gherkins, SpecFlow, Living Documentation, features and so on, often meaning the same thing. So far this had not been an issue for us within the immediate development team – we knew what we meant. But we realised quickly that it confused our stakeholders, who had never heard those terms before and that we needed to speak more clearly and share more information about terminology and process with them.

One thing we had already established amongst the development team was a “Gherkin Agreement”, where we defined what we want to achieve with our Living Documentation and how we meant to use it. We stored this information in our project documentation/wiki. It mostly got used to onboard new team members and to align on our process.

After some of these confusing meetings with our customers, we realised that they needed the information we already had in our “Gherkin Agreement” – they essentially are new team members in this situation. After a little brush-up and making sure we used consistent wording, we added the “Gherkin Agreement” to our Living Documentation, which our customers could access.

Over the course of the project, we extended this part of our Living Documentation whenever necessary. In the end it contained the following information:

- Purpose and goals of this Living Documentation

- Characteristics of a BDD scenario

- How to use BDD scenarios for manual testing

- Which application state this Living Documentation reflects

- How to check test results of this Living Documentation

- Glossary of terms with special meaning:

- Tags

- Values

- Words

Purpose and goals of this Living Documentation

This section helps explain to your readers, what Living Documentation means. It also helps align project team members to why a Living Documentation approach was chosen and can list consequences for implementation.

For example, in our project we documented that one goal of our Living Documentation was to be used for acceptance testing by our stakeholders. For this it had to be readable and understandable by everyone (not just people with technical knowledge of the system).

The second goal we documented was, to keep a single source of truth. This meant documenting system behavior within our Living Documentation, even if we didn’t intend to automate it.

Characteristics of a BDD scenario

This part explains the purpose of each keyword, so stakeholders know what to do with it, when manually checking a scenario.

We could have linked to an external source describing the Gherkin language. But we wanted to save our customers to have to read through too much information on that topic and potentially get further confused. So, we documented this short version of it:

A scenario describes how the system should behave, instead of single test cases. Meaning a scenario title represents a system specification or acceptance criteria. In order for the behavior to be automated, we use the Gherkin language, consisting of three blocks (Given, When, Then).

- Given steps describe the state of the system with which we begin (Arrange)

- When steps describe the action which triggers the systems behavior (Act)

- Then steps describe the behavior or state of the system which needs to be checked (Assert)

How to use BDD scenarios for manual testing

Having worked as an agile tester with BDD and automation for a while, I know that for better readability of a scenario we sometimes omit values if they are not relevant for the described behavior. I know, when I manually test a scenario, that I might also have to prepare necessary data or fill out mandatory fields even if not mentioned explicitly in the scenario. This is a big difference to test case specifications, where inputs and preconditions are explicitly stated. Stakeholders who have never worked with this kind of documentation before don’t know about this difference. So we explained this in this part of the documentation.

Which application state this Living Documentation reflects

In feedback sessions with the customer, we found out, that they were confused by looking at Living Doc because features, that were discussed but were not implemented yet, were missing from the Living Documentation. We explained in this section, that the Living Documentation delivered at any time, describes the system behavior at that point in time and not the full scope of features or the project that is still in work. We also stated clearly that the documentation will grow and change after feedback cycles as the project progresses.

How to check test results of this Living Documentation

A question that was brought up by our customer was “does the system really behave like described in the documentation”. To answer this, we explained that by automating scenarios we receive immediate feedback, if the application behavior was broken or still works as expected. It took a few demos of the automation to get them to trust these test results, but once this was established the process excited our customer a lot. Needless to say, from now on our customer only wanted to start acceptance testing when the system had gone through testing on our side and was in a “green” status.

You can easily show the test execution results in SpecFlow+ LivingDoc with every delivered version:

Glossary of terms with special meaning

Tags

As part of our internal “Gherkin Agreement”, we documented the meaning of tags used throughout our Living Documentation. This information was also very relevant for our customers during testing.

For example, our customer asked us what “DocumentationOnly” on top of some of the scenarios meant. We used this tag on all scenarios which were not automated. We did this to

- quickly find scenarios which need to be checked manually

- quickly find scenarios which need to be checked before releases if the information is still up to date

- exclude these scenarios from build execution

- control if these scenarios appear as failed, skipped or passed in local test executions (see Scoped Step Definitions)

Also, the tag “ClarifyWithCustomer” meant, that there were still open discussions to parts of the described behavior. So, when costumers came across a scenario with this tag, they knew it’s most likely going to change and that they don’t need to spend time on testing it yet.

Values

Within the team we agreed, that when a hyphen “-“ is used as a value in a scenario, that its property is NULL. We could have just left the value empty, but it often was not clear enough that way. It could have meant NULL, empty string or simply did not fill out the value yet. Our customers needed to know what we meant exactly so they could test properly – and for them it should mean that the according UI field is left empty.

Words

To make the automation tied to our steps more explicit and re-usable, we used specific words for specific implementations of step definitions. For example, if we wanted all entries of a list checked we used the following step formulation:

- “Then in the student list the following students exist:” followed by a table listing all entries.

If we only wanted to check if a list contains certain elements, we used the following formulation:

- “Then the student list contains the following students:” followed by a table listing only the students we want to assert our scenario with.

For the development team the different wording made a difference what to assert for and for our customers this information was relevant, so they knew what to expect as a scenario outcome.

Living Documentation needs to be current, complete, and accessible

Stakeholders usually don’t have a Visual Studio license nor the appetite to browse Feature Files in a developer’s tool. Simply handing over the Feature Files is not enough to be able to efficiently use Living Documentation for testing. This job requires a tool that allows stakeholders to partake. SpecFlow currently provides 2 options:

SpecFlow+ Living Doc on Azure DevOps

You can provide your customers with stakeholder access to Azure DevOps. This way they can access your Living Documentation generated by your build pipelines and hosted on Azure Devops. If you choose to grant access in this way – it is important to note – that customers will then have access to all your generated Living Documentation from all your repositories and branches. So your customers need to know exactly which repository and branch to select, in order to see the version intended for them (see screenshot in the specflow documentation).

SpecFlow+ LivingDoc CLI Generator

SpecFlow recently released SpecFlow+ LivingDoc CLI Generator. If I were to start my project again today, I would definitely pick LivingDoc CLI Generator over Azure DevOps because it allows me to generate exactly the version of the Living Documentation that is intended for the customer as a html file. This way there is no risk anymore that non familiar users get lost by looking for information in the wrong places. I would even go further and add the intended use of this report to its title (e.g. the upcoming Clarification Meeting).

Where to put the “Gherkin Agreement” now exactly?

Scenarios are stored in feature files as part of the source code. In our project we grouped them in a folder called “Features” to indicate that this section contains all documentation concerning the behavior of the system.

We wanted a clear separation of the description of the systems behavior from the explanatory part of the documentation. So, we added a folder “Information about this Living Documentation” on the same level as the “Features” folder. In the folder we added feature files, using the feature title as section header and the feature description to store the information in cleartext (with some markdown for formatting). This was the perfect place for our customers to read up on how to interpret the information they are going to read in the “Features” folder.

Conclusion

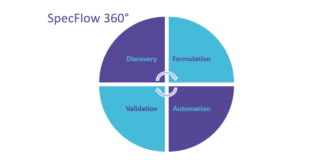

One of the core principles of Living Documentation is Collaboration:

“Favor conversations over formal documentation: Nothing beats interactive face-to-face conversations for exchanging knowledge efficiently.”

(“Living Documentation – Continuous knowledge sharing by Design” by Cyrille Martraire, p21)

All the things described in this article were not only solved through documenting them in Living Documentation, but by introducing them to our customers in review meetings, demos and testing workshops. Sometimes in bigger groups of up to 15 people, sometimes only with the heads of the department who then briefed their teams on the workflow before acceptance tests started. The “Information about this Living Documentation” section hardly ever changed and was therefore cheap to maintain. Its biggest use was to establish a common understanding of our way of working together on this project. It showed me how important it is to not circulate information to a wider group of people without setting its context properly at the same time.

With our Feature File structure and naming of Scenario Titles (part 1), we achieved a comprehensible Living Documentation, that allows stakeholders to quickly sift through a huge amount of information. Providing our stakeholders also with further details about Living Documentation itself (part 2), truly enabled them to use it for their user acceptance tests and implementation sign-off. I hope, these 2 articles will save a few more people out there from having to write tedious test case specifications and enables them to re-use their hopefully already existing Living Documentation for it instead.