How do I share multiple scenarios between feature files?

The challenge is to deal with seemingly redundant information, where the same scenarios are used for several different purposes.

How do I share scenarios between feature files?

Here is the challenge

There are a few situations when this kind of sharing is useful.

When doing platform migration projects, the old and the new system usually have almost the same functionality. For a period of time, both systems may need to be operational, so people usually want to test both of them. In cases such as these, the set-up and the contents of the scenarios are almost the same, with some minor variations, but the execution differs significantly because steps need to run against two different systems. A typical way to achieve this with Given-When-Then would be to use scenario outlines, where the example tables are the same, but the scenario bodies differ.

When two modules of a system have very similar (or identical) functionality, the scenarios describing those two functional areas will be very similar. For example, I worked on a banking platform where the client wanted to start trading with Canadian equities. The mental starting point for business users was to replicate the functionality for US equities, since the rules were sufficiently similar, and then start modifying them. In cases such as these, the set-up is different, and some minor scenarios will differ, but most of them will be the same.

When the business domain model and the technical model differ significantly, business users may want to prove test coverage by executing almost the same scenarios for different classes of inputs. In cases such as these, the set-up for the scenarios is different, but the rest is usually the same. For example, business users at a client of mine wanted executable specifications to show how foreign exchange contracts are executed for all the most important currency pairs. There were hundreds of scenarios across dozens of feature areas that would need to be executed and demonstrated to the business users for review. Apart from starting with different currencies, there was very little difference between them. The variations were mostly related to rounding as different currencies have different rounding rules. The underlying code was actually the same the scenarios always executed against the same service but because of business risk the client wanted to run tests for all the key currency pairs.

The problem in all such cases, and the reason why people want to share scenarios across feature files, is to reduce maintenance costs. When the scenarios are sufficiently similar, changing something in one group usually means that it needs to change in all the other groups as well. This becomes tedious and error-prone when the same data is copied in multiple places.

Your challenge is to propose ways to reduce the maintenance overhead of working with duplicates, but still allow the same scenarios to run multiple times, with different set-up information, or different ways of executing the scenarios.

Solving: How to deal with groups of similar scenarios?

The challenge was to work effectively with groups of similar scenarios, which need to use the same values, but in different structures.

Scenario outlines are the usual way of reducing redundancy, but they will not work for this situation. Outlines make it relatively easy to run the same scenario for a combination of values, for example:

Scenario Outline: New forex contract for valid currency

Given a forex contract for currency

When the contract is received

Then the contract status should be "Open"

Examples:

| Currrency |

| EUR |

| USD |

| GBP |That’s a great way to reduce duplication for a group of scenarios that essentially shares the same structure. But what if we want to run hundreds of different types of scenarios with the same three currencies? Scenario outlines are no longer a good solution. The currency list itself would become massively redundant, copied into hundreds of places. Updating the list to add another currency would be a big problem.

FitNesse solved this issue with symbols and test suites that could dynamically include other test suites. It was easy to create one common set of scenarios using a symbol (say $CURRENCY), and then include that set in three different test suites. Each top-level suite would just set up the symbol to use a specific currency, and point to the included tests. The scenarios would be in a single place, and the definitions for each currency would be in a single place. Adding a new currency, or removing one, was be quite easy. With most Given-When-Then tools, this is not so easy, but there is a good workarounds using templates. Although SpecFlow does not support symbols and linked suites directly, it does have a few tools that make it possible to implement very similar functionality. In this post, I’ll explain both the generic approach, and a SpecFlow-oriented solution.

Use template files

Most Given-When-Then tools look for files with a .feature extension, and ignore all other files. That allows us to create a set of template files to hold our generic scenarios, which would not be immediately visible to the test runner. For example, create a forex.template file that uses special placeholders for dynamic values, such as the following snippet:

Scenario: New forex contract for valid currency

Given a forex contract for currency {{CURRENCY}}

When the contract is received

Then the contract status should be "Open"The project builder could use a list of parameter combinations to generate feature files before even running SpecFlow. It would look for any files with a .template extension, fill in the placeholders, and save the results under a sub-directory based on the parameter. For example, forex.template could be saved in the USD directory as forex.feature, with the replaced contents:

Scenario: New forex contract for valid currency

Given a forex contract for currency USD

When the contract is received

Then the contract status should be "Open"The build job would similarly create EUR and GBP subdirectories with processed templates, replacing the placeholders accordingly. SpecFlow can then run tests using the processed files, and execute scenarios for all three currencies.

There are ready-made template file processors for Gherkin out there. For example Ken Pugh’s Cucumber Preprocessor handles this case with #define. The generic functionality often means you lose some flexibility around how to structure files, so it might be worth creating your own processor. It’s not that difficult to make it with an open source template engine. I quite like using Handlebars (hence the {{}} syntax in the previous example), and there are many other options making this a fairly simple task.

Use SpecFlow argument conversions

The template file solution works with all Given-When-Then tools, but SpecFlow also has a few native tricks that simplify this process. Instead of applying a template before a test run, you could use Step Argument Conversions to fill in placeholder values during the test execution. This simplifies the process significantly, since you no longer need two sets of files.

Step argument conversions modify the arguments of a step after the SpecFlow engine reads the Given-When-Then text, but before they get passed to automation bindings. This allows us to use generic arguments in the scenarios, and replace them with actual values for the step implementation. Because the step arguments will be transformed on the fly, we just need to somehow mark template placeholders so that they are easy to find. For example, enclose the placeholder names in {}. (Resist the urge to use < and >, as SpecFlow will look for a scenario outline value for those.) The scenarios could then just use the placeholder currency, such as in the next snippet:

Scenario: New forex contract for valid currency

Given a forex contract for currency "{Test_Currency}"

When the contract is received

Then the contract status should be "Open"We can now easily run the test suite multiple times for different variables. For example, we could store the currency in an environment variable before executing SpecFlow, and write an argument conversion that matches arguments enclosed in {} against environment variables. The following snippet does just that:

[Binding]

public class TemplateArgumentsTransformation

{

[StepArgumentTransformation(@"^\{(.*)\}$")]

public string HandleTemplateArguments(string placeholderName)

{

return Environment.GetEnvironmentVariable(placeholderName) ?? $"{{{placeholderName}}}";

}

}With this tool in hand, you can add templated placeholders to your SpecFlow tests easily. Just make sure to set the environment variables before actually running the tests.

Use SpecFlow targets

For a fully automated solution, we can combine step argument conversions and another SpecFlow feature: test targets. You can set up multiple test targets in your SpecFlow runner profile, and it will run the tests once for each defined target. This allows us to automatically run the same test suite multiple times, with different set-up values.

Targets can even configure environment variables for a test run automatically, making it easy to apply the previous argument transformation. Here is an example of a runner profile setting two targets, with different values for the Test_Currency environment variable:

Setting up targets as in the previous snippet would cause SpecFlow to run the entire test suite multiple times, even the scenarios that do not depend on any templates. For faster execution, we could tag the scenarios that require currency templating with @CurrencyTemplate, and then include this tag in the target filter. The following snippet shows how to set up three test targets – two with a template, and one for scenarios that do not need template conversions:

@CurrencyTemplate

...

@CurrencyTemplate

...

!@CurrencyTemplate

...

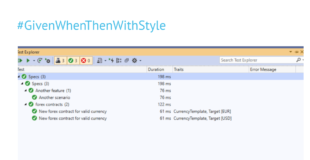

This runner profile would execute all the tests without the tag once, but make sure that the currency template tests execute once for each currency. A sample test report would show the execution for individual targets, as in the following screenshot:

Choosing the right option

The benefit of the template option is that you can actually see the values in the files after execution, but the downside is that it requires a bit of discipline with editing. People must not edit the generated feature files, but only the templates. This could become messy if you mix templated and non-templated feature files in the same directory. My suggestion is to use some directory structure that clearly separates generated and original files, so that the processed feature files never end up in your source code repository.

The benefit of using argument transformations (especially with targets) is that you only have one set of files, so there is no chance for confusion, but the downside is that you no longer see the actual values in the source files. The replacement happens under the hood. The test results will show the applied value. For more confidence you could log the actual value to the console in the steps, or during the transformation. That way, the console logs will show next to steps in test results, and you can inspect what actually happened.

If you use SpecFlow, I’d suggest using the transformation option inside the runner, unless your business people insist on having multiple copies of the templated tests. If you use a different tool, that does not have an equivalent feature, you may need to use the template files option instead.

To dig deeper into the code required to run the transformations, check out the sample project on GitHub. The project contains a fully functional setup for the solution of this challenge, including step argument transformations, test targets setting environment variables and running the test suite multiple times with different environment variables.